An article for OkayAfrica on new Ghanaian fashion line Raffia, which is steadily dismantling stereotypes about Ghana's Northern Region. Find the original article here or read below.

Far from the flashing lights of Accra, Northern Ghana might be the surprising new locus of a growing market for African fashion. While the Gold Coast is well-known for kente cloth, a richly patterned fabric that Ghanaian royals have sported for centuries, gonja cloth, its northern cousin, has yet to make a splash on international markets—until now.

Madonna Kendona-Sowah, founder and creative director of new fashion line Raffia, knows that there’s more to West African fashion than Ankara and kente cloth. Raffia produces high-quality clothing made from the woven material made in Northern Ghana.

Now in its second season, Raffia plans to dispel stereotypes that Ghanaians in the country’s wealthier, southern region have about their Northern countrymen. According to Kendona-Sowah, “Because of poverty, Northerners are considered to be less educated or enlightened. I think that perception is largely because it’s far away and most Ghanaians don’t travel widely throughout the country.”

The line’s name comes from the Raffia palm, which like Northern Ghana, is “rough and dry in its raw state but can be used to make beautiful things.”

Northern-born Ghanaians are vastly underrepresented in Ghana’s burgeoning high-street fashion scene led by designers like Christie Brown, Mina Evans, and Duaba Serwa. From the colonial days of gold mining to the present, the Akan people have dominated the country’s business elite. “Northern Ghanaians, even those who are well educated, will aspire instead to be civil servants. One of the things people told me when I decided to start Raffia was, ‘We’re not really entrepreneurs. That’s not what we do,'” Kendona-Sowah says.

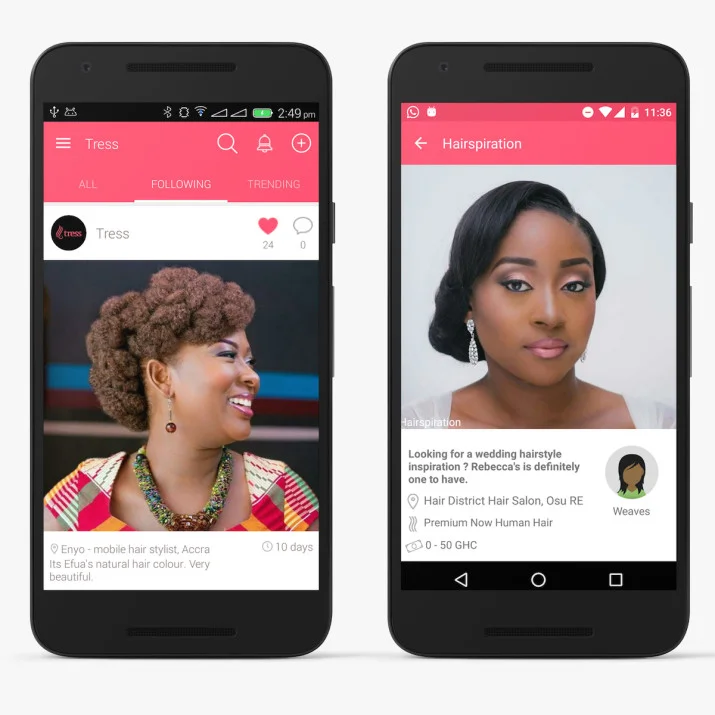

Some raffia designs at the atelier opening in Accra.

Until now, shea butter is likely Northern Ghana’s most well-known export. Raffia hopes to add gonja cloth to that list. Made from cotton, gonja cloth is carefully dyed and hand-woven. Unlike its younger, southern cousin kente, which tends to feature bolder colors, gonja cloth traditionally uses more subdued tones like blue, brown, and black. In contrast to the wax print market, which is dominated by Dutch-owned Vlisco and Woodin and a growing flood of Chinese-made products, kente and gonja are still almost exclusively produced in Ghana. A growth in demand for these high-quality local materials could help the struggling Ghanaian textile industry.

Gonja cloth, also popularly known as batakari, can also be distinguished from kente cloth in another unique way—the gender of its weavers. Traditionally, men weave kente, but in Northern Ghana, Kendona-Sowah tells me, “You’ll see women weaving when they have time off.”

The budding designer works with an all-women cooperative in Zuarungu, Upper East, who produce her range of originally designed fabrics. As a social enterprise, Raffia focuses on professionalizing the women’s work and enhances their quality of life to enrich their families and communities.

Madonna sketching a bespoke design for a client.

Raffia’s beautiful range of skirts, blazers and crop tops might be shock to those familiar with gonja cloth, which is usually only found as a smock or kaba and slit. Kendona-Sowah attributes the limited range of traditional designs to the cloth’s standard use as a utilitarian piece of clothing. “My mother and aunties, who are very fashion-forward, never even used the fabric to make dresses. It was just skirts and tops,” she tells me.

“People haven’t seen the high fashion potential, but I’ve always loved the fabric as a child. When I decided to go into fashion, I wanted to do something high quality. Knowing about the fabric, how it’s woven with such attention to detail, but has always had a low profile made it a no-brainer when I decided to create the line.”

The line is the culmination of a long-held dream of being a fashion designer. After interning for a designer at 18, Kendona-Sowah deferred her aspirations in favor of a career in international development. When she turned 30, she decided it was finally time to pick up the sketchbook again.

In the two short years since Raffia launched, it’s seen remarkable success. In 2015, Kendona-Sowah was selected as one of 1000 Tony Elumelu Entrepreneurship Program (TEEP) 2015 entrepreneurs. The line is now stocked at London-based store Sapelle as well as Accra’s Elle Lokko, a picturesque concept store that recently opened in the bustling neighborhood of Osu.

With more retailers coming on board this year and a steadily growing clientele, Kendona-Sowah opened a Raffia atelier this March in Accra to give customers the space to meet her with her to discuss fabrics and bespoke designs. While Raffia does have an online shop, a full-scale shop in Accra is much further down the pipeline. “At this point, I want our team to concentrate on growing the brand, cultivating our customer base, and growing as creative—hence the atelier space,” she says.

As Raffia continues to grow, Kendona-Sowah hopes that the brand’s expansion helps the women at the foundation of the business. “To me, social enterprise is having the development of the community you work with in mind as you grow your business. There wouldn’t be Raffia without community development. As we grow, they will grow.”