Antonia Opiah just wanted to get her hair done. As she prepared to go on vacation, the serial entrepreneur struggled to find time to have her hair braided between the demands of work. “I wished that someone could come to my house and do my hair, she lamented, “so that I could feel justified spending time on my hair by being simultaneously productive.”

In New York City, there are a handful of apps from Glam Squad to Priv that allow stylists to come to you, but they primarily cater to white women. In researching better at-home hair options, Opiah asked her sister Abigail to try out a few existing options. The results were disappointing. When Abigail booked an appointment with one of the services, the stylist arrived not knowing where to begin. After poking around her hair, he took a picture for his records.

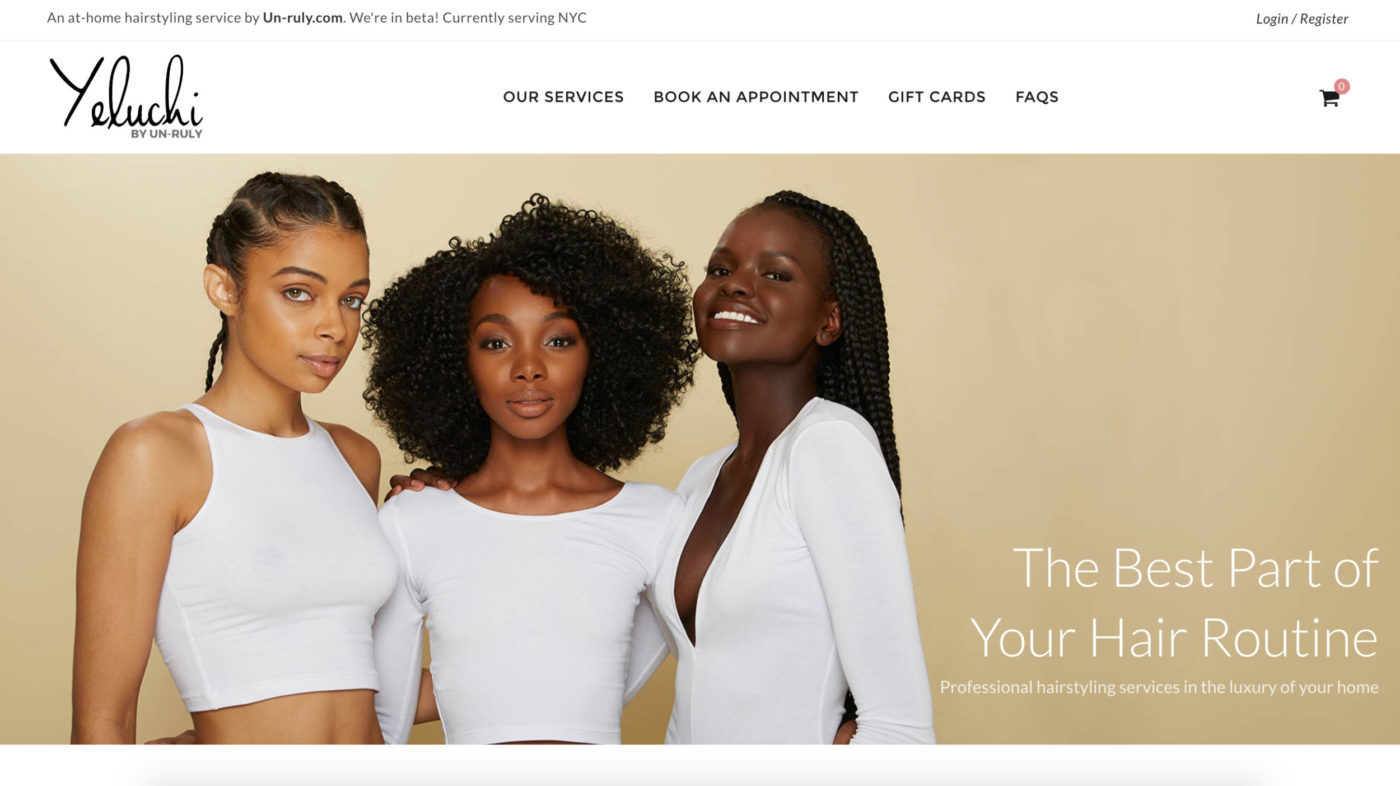

“Abigail’s experience confirmed for us that these services aren’t catering to black women, so we decided that there was space in the market.” Opiah says. In March 2016, the sisters jointly launched Yeluchi by Un-ruly, which focuses on bringing the salon experience to the homes of black women.

The service is an extension of Un-ruly, a website that celebrates the beauty and versatility of black hair. Opiah founded Un-ruly in 2013 as a kind of online beauty shop—a space where women could come together to discover hair and their day-to-day lives. “Like many black women, I change my hair pretty frequently,” Opiah says. “When I started Un-ruly, I wanted a nicely designed website where I could find inspiration for my next hairstyle.”

Un-ruly breaks down the ins and outs of every hairstyle under the sun—from natural hair to wigs and extensions. Opiah and her team of contributors live and breathe hair. They capture street style inspiration and write about healthy hair care regimens; they reflect on society’s beauty standards. Yeluchi builds on the impressive knowledge base that Opiah has built through Un-ruly to help its clients pursue a happy hair journey.

The name of the service, Yeluchi, is a play on Opiah’s own Igbo name, Chinyelu, meaning “God’s gift.” To Opiah, choosing a name with such a powerful meaning was not only a way to leave her mark on the business, but also to challenge perceptions of black hair as difficult.

As the sisters have rolled out the service, it hasn’t all been smooth sailing—there are several unexpected surprises. Despite the limited menu of hairstyles, for example, clients routinely ask for variations on simple styles like ends curled or edges laid a certain way. To Opiah, this is not so much a challenge as it is an affirmation of the versatility of black hair. “You can’t put it in a box no matter how hard you try.”

Now operating across New York’s five boroughs, Yeluchi boasts a network of top quality stylists who cater to a menu of protective styles like braids and weaves. Prices range from $50 for a simple cornrow style to $300 for the waist-length box braids of #carefreeblackgirl fame. With bookings taking place primarily online and a small network of stylists, Yeluchi aims to grow slowly to achieve quality service before expanding its reach in New York and to other cities. While an app is planned down the line, Opiah is in no rush.

“The service comes first, and we want to understand our customer because we’re seeing that there are so many nuances that go into styling black hair,” she says. “We’re prioritizing the service before creating the app because the app is just a vehicle for the services people are purchasing.”

As consumers become more accustomed to an “Uberized” environment, Yeluchi stands apart from the rest of the gig economy as more than just a service. With the support of the Un-ruly platform, Opiah has created a product that is not only revolutionizing the notoriously time-intensive nature of protective styling, but also educating consumers on their hair’s endless possibilities.