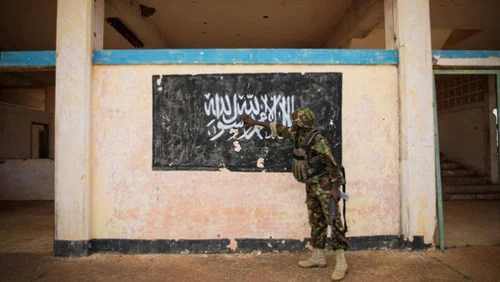

(Image: Kenyan soldier points to the black flag of the Somali militant group Al-Shabab)

In the wake of Westgate, Mpeketoni, Kapendo and Mandera, Kenya is a nation at war. As the country struggles to mount an appropriate response to the rising Islamist threat, new proposed legislation threatens to erode progress made in recent decades.

Since last month, Al-Shabab has killed 64 people in two separate attacks in Mandera. On November 21, attackers boarded a Nairobi-bound bus and massacred 28 passengers unable to recite an Islamic creed. On December 1, Al-Shabaab fighters killed 36 people in Mandera, again discriminating on the basis of religion.

Following bitter debate, the Kenyan Parliament recently passed a counterterrorism bill during a session in which MPs nearly came to blows and even tore up pieces of the proposed bill. Leading Kenyan media outlets labelled Parliament “a house of shame” as papers and insults flew threw the air over calls for order.

Dismissing domestic and international criticism over the controversial piece of legislation, President Kenyatta quickly moved to sign the bill into law. The United States State Department issued a statement regarding its concerns on the legislation’s provisions and cautioned the Kenyan government to respect civil liberties and international norms. Munyori Buku, a senior official at Kenya’s state house, issued a swift and curt response to the United States on the president’s website, saying that Kenya’s new law has checks and balances unlike U.S. security laws that have given U.S. FBI and intelligence officers “a carte blanche in the fight against terrorism and biological warfare.”

Americans who remember the terrible events of 9/11 may naturally sympathize with Kenyans’ current plight. Like the United States Patriot Act of 2001, the Kenya Security Law was passed in response to deadly attacks that shocked a nation. For the US, it was 9/11; for Kenya, the final trigger was the recent Mandera attacks. Exploiting the climate of fear, the Patriot Act, like the new Kenya Security Act, swiftly moved to strengthen anti-terrorism measures. However, their are crucial differences between the two pieces of legislation. The new Kenya Security Act goes far beyond the Patriot Act by infringing on basic civil liberties and potentially violating the country’s newly-revised constitution.

While Mr. Buku may be correct in his assertion that the Patriot Act did result in widespread and well-documented abuses that sparked political scandals (e.g. Snowden, Guantanamo abuses and the CIA torture report), it featured accountability mechanisms and was open to public discourse. US Congressional re-authorization of the Patriot Act every four years acts as a safeguard. As a result, the more controversial aspects of the Patriot Act have either been amended, repealed or have expired. In contrast, the Kenya Security Act does not include similar provisions and awards too much much power to Kenyan security agencies and officials at the expense of the rights of its people.

Risk that the massive expansion of surveillance powers will be abused to justify investigations of political dissent or low-level offenses is high. The bill would expand powers of intelligence officers that were reduced in the 1990s following accusations that the Special Branch (now the National Intelligence Service or NIS) tortured activists and opposition leaders and detained them without trial. For many Kenyans, many of whom are still prominent opposition figures in Kenya today, these painful memories of the Moi years are still fresh. Thus it is no surprise that opposition leaders mounted such a fierce dissent to the legislation.

Concerns over abuse are well-founded in light of the Anti-Terrorism Police Unit (ATPU)’s long history of human rights violations. The ATPU has been linked to numerous disappearances and extrajudicial killings in the name of combatting Al-Shabbab. These abuses of power are highlighted in the recent Al Jazeera documentary Inside Kenya’s Death Squads, whichfeatures four units of Kenya’s counter-terrorism apparatus admitting that police assassinated suspects on government orders.

Empowering agencies that have shown such prior proclivity to shirk the law signals a retreat from accountability, justice and rule of law. Such action is dangerous in light of the Security Act’s often vague, ambitious and broad provisions.

The Act’s most controversial provisions include the following:

- Article 18: enables police to extend pre-charge detention for up to 90 days with court authorization. Kenya’s current law limits detention to 24 hours.

- Article 19: prosecutors do not have to disclose evidence to the accused if “the evidence is sensitive and not in the public interest to disclose.”

- Article 58: caps Kenya’s refugee population at 150,000

- Article 66: enables NIS officers to carry out “covert operations,” broadly defined as “measures aimed at neutralizing threats against national security.”

- Article 75: prohibits broadcasting any information likely to undermine investigations or security operations without police authorization and prohibits publishing or broadcasting photographs of victims of a terrorist attack without police consent

As we face the scourge of terrorism in the technological age, there are undoubtedly tradeoffs between privacy and security, however, adequate checks and balances must be established. Currently, under the new law, the NIS has unlimited powers to tap telephones without court order. In the vast majority of democratic countries - including the United States, which has one of the most aggressive counterterrorism programs in the world- such action requires a court order. The right to privacy should be respected by deferring to provisions in the Kenyan constitution that require warrants in such circumstances.

For Kenya’s 530,000 refugees, the Act has particularly serious implications. If Kenya’s refugee number is capped at 150,000, refugees will likely face refoulement. Under the new law, Kenya would be forced to expel refugees and asylum seekers. Such action would directly violate Kenya’s Refugee Act of 2006 as well as international laws including the OAU Refugee Convention.

As written, the Act tacitly makes the assumption that civil liberties such as freedom of expression and freedom of the press are an obstacle to enforcing security rather than a boon to the state's efficiency and accountability mechanisms. Instead of restricting civil society, the Kenyan government should consider enforcing existing laws aimed at combatting incompetence within the security force. The dismissal of former Interior Joseph Ole Lenko and the early retirement of former Inspector General David Kimaiyo have been good first steps, however change cannot stem from the mere shuffling of administrators. Rather, there must be a systematic approach to reforming Kenya’s security and intelligence forces.

Last month, protestors poured into the Nairobi streets to express their frustration over government’s failure to protect its citizens in a movement called Occupy Harambee. Today, Kenyans need harambee more than ever now to protect their civil liberties and to ensure that the country progresses rather than regresses to the police state of the 1980s and 1990s.

On December 23, Kenya’s opposition coalition took the first step towards such action by filing a court challenge to overturn the law. It is now up to Kenyan civil society leaders to continue to raise their voices in the press, in their communities on the streets to demand that a better balance between security and liberty.