Take a look at Yale Daily News coverage of my efforts (with the help of my great classmates Emma Goldberg and Dianne Lake as well as the Yale Women’s Center) to bring attention to Equal Pay Day in New Haven.

Equal Pay for Equal Work

Originally published in the Yale Daily News on April 14, 2015.

For graduating seniors, starting salaries are an all-too-common concern, but for soon-to-be alumnae, figuring out next year’s salary may be a little more stressful than for our male counterparts.

From Patricia Arquette’s Oscar speech on the gender wage gap to the recent controversial ruling against Ellen Pao in her gender discrimination lawsuit, women’s rights in the workplace have been a hot topic in the last few months. And rightly so. Today, women make 78 cents for every dollar a man earns, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

The median weekly earnings for American female doctors working full-time is $1,497 versus $2,087 for men. Women in architecture and engineering earn 83.7 cents to a man’s dollar. The gender pay gap stretches across almost every industry. Even in nursing, a profession where women outnumber men 10 to one, men out-earn women by nearly $7,700 per year in outpatient settings and nearly $3,900 in hospitals. From blue-collar to white-collar jobs, women aren’t getting equal pay for equal work.

While the world these days tells us to “lean in,” it isn’t all that simple.

The wage gap stems not only from the persistent underestimation and under appreciation of women’s contributions in the workplace, but also from stigma surrounding salary negotiations.

Even if a woman knows her worth, negotiating a salary can come with a cost. For years, studies on salary negotiation have shown that the social cost of negotiating for higher pay is greater for women than it is for men. Before we chime in to criticize women for not “leaning in,” we must recognize that women’s hesitancy to ask for a raise often stems from an intuitive sense of the risks.

But the burden of advocating for equal pay should not be shouldered by women alone.

We can start by recognizing women’s worth in the workplace. According to popular gender stereotypes, when men are assertive, they are often called “leaders.” When women do the same, they risk being labeled “bossy” or “pushy.” Men are expected to be ruthless and women nurturing. Because we expect women to fulfill the “mother hen” role, we are less likely to reward them for being a team player.

A recent study by New York University psychologist Madeline Heilman found that male employees were continually viewed more favorably than women when giving the same help to a colleague. As Sheryl Sandberg recently noted in The New York Times, this means that women “do the lion’s share of office housework” — with little recognition. It’s time to acknowledge the contributions of women and compensate them fairly. Men can help by volunteering to take over some of the group tasks. By doing so, we can give women more opportunities to have their voices more fully heard.

Ellen Pao, interim CEO of Reddit, has a rather innovative idea for the private sector: eliminate the salary negotiation process entirely. In a recent interview with the Wall Street Journal, Pao noted that “men negotiate harder than women do and sometimes women get penalized when they do negotiate.” Most government jobs have fixed salaries based on title and years of experience. Because these salary rates are public information, workers can easily compare pay, reducing the likelihood that bias will impact compensation. Thus, it should come as no surprise that the wage gap is considerably smaller in the public sector. According to the Office of Personnel Management, between 1992 and 2012, the gender pay gap for public sector workers fell from 30 percent to 13 percent for white-collar workers and 11 percent for General Schedule workers.

Finally, we can more directly confront our unconscious biases. Everyone has them. Taking an Implicit Association Test will quickly disabuse you of the notion that you are the most forward-thinking, progressive person at work. And that’s okay — as long as you work at recognizing and correcting these preferences. Google is a great example of a company at the forefront of this movement in the tech industry. Google made efforts to encourage its employees to confront their biases with the hope that that awareness could help level the playing field.

Today, women make up the majority of college graduates and hold the majority of management and professional positions, but according to the World Economic Forum, I’ll be 102 years old by the time the gender wage gap closes in the United States. While laws like the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009 are a good first step towards equal pay, they clearly aren’t the only solution. In order to make sure women are recognized for the vital role they play in the home and the workplace, we must confront the problem at hand

On Biram Dah Abeid and Slavery in Mauritania

Which country was the last nation in the world to abolish slavery? Unbeknownst to most people, it was Mauritania in 1981. However, despite bowing to international pressure and allowing slaveholders to be prosecuted, Mauritania continues to struggle with slavery.

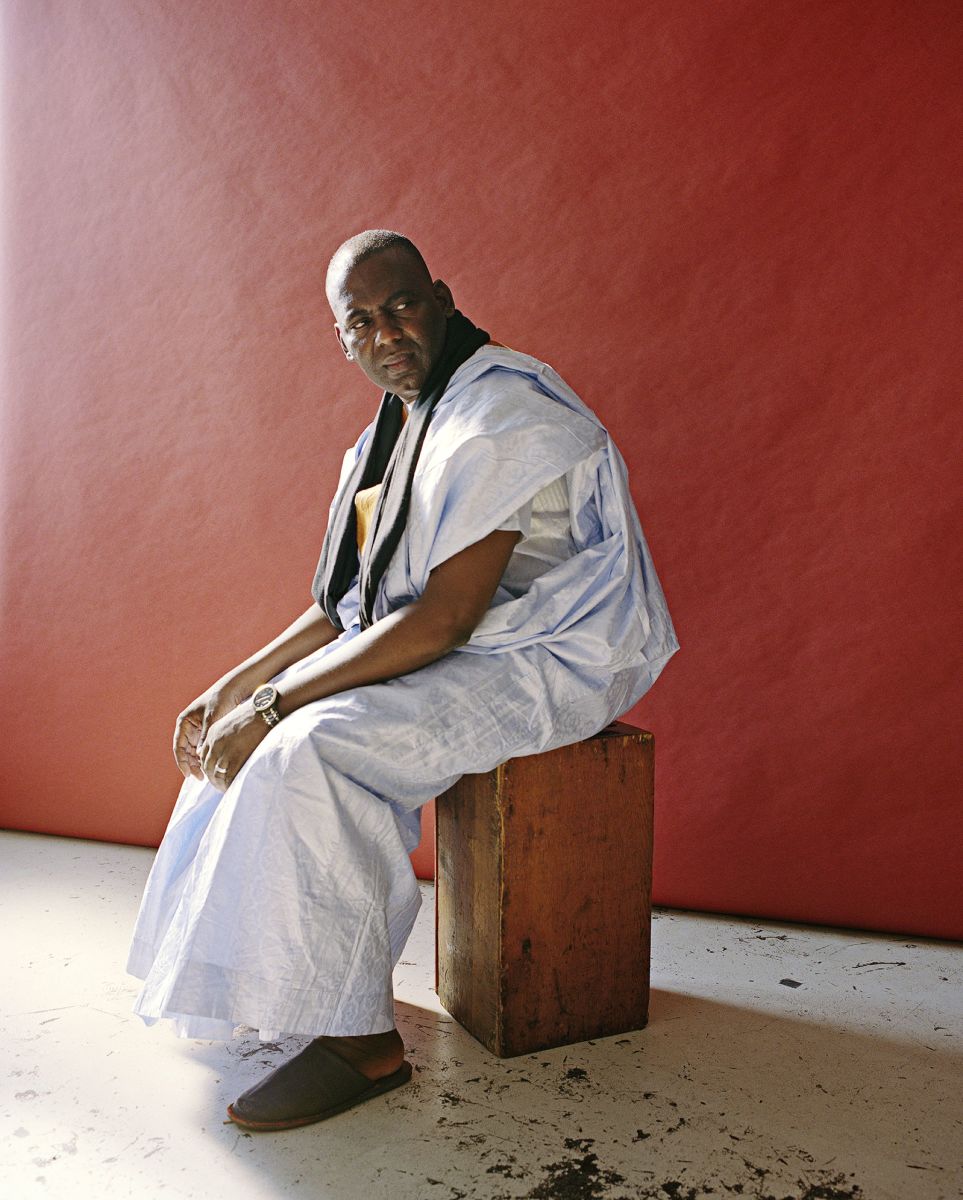

Biram Dah Abeid is Mauritania’s leading abolitionist. Through his organization the Initiative for the Resurgence of the Abolitionist Movement, he has fought for the freedom of countless men, women and children.

But today Mr. Abeid is imprisoned. On 11 November 2014, Biram Dah Abeid and eight of his colleagues from the Initiative for the Resurgence of the Abolitionist Movement were arrested following their participation in a caravan of protest organised by the IRA and other NGOs calling for the abolition of slavery in Mauritania.

Learn about Abeid’s work here:

- “Freedom Fighter: A slaving society and an abolitionist’s crusade"

- ”A Modern-Day Abolitionist on Fighting Slave Power“

- ”Slavery: still trapped“

- 2014 Geneva Summit: Biram Dah Abeid, Mauritanian Human Rights Activist

Sign this petition and help mount international pressure for his release.

A Patriot Act for Kenya?

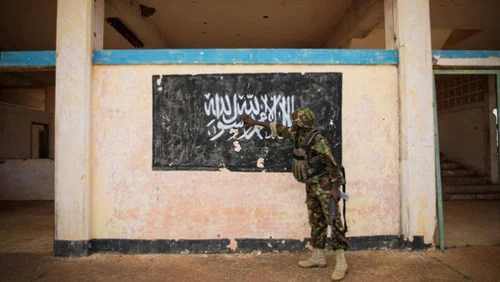

(Image: Kenyan soldier points to the black flag of the Somali militant group Al-Shabab)

In the wake of Westgate, Mpeketoni, Kapendo and Mandera, Kenya is a nation at war. As the country struggles to mount an appropriate response to the rising Islamist threat, new proposed legislation threatens to erode progress made in recent decades.

Since last month, Al-Shabab has killed 64 people in two separate attacks in Mandera. On November 21, attackers boarded a Nairobi-bound bus and massacred 28 passengers unable to recite an Islamic creed. On December 1, Al-Shabaab fighters killed 36 people in Mandera, again discriminating on the basis of religion.

Following bitter debate, the Kenyan Parliament recently passed a counterterrorism bill during a session in which MPs nearly came to blows and even tore up pieces of the proposed bill. Leading Kenyan media outlets labelled Parliament “a house of shame” as papers and insults flew threw the air over calls for order.

Dismissing domestic and international criticism over the controversial piece of legislation, President Kenyatta quickly moved to sign the bill into law. The United States State Department issued a statement regarding its concerns on the legislation’s provisions and cautioned the Kenyan government to respect civil liberties and international norms. Munyori Buku, a senior official at Kenya’s state house, issued a swift and curt response to the United States on the president’s website, saying that Kenya’s new law has checks and balances unlike U.S. security laws that have given U.S. FBI and intelligence officers “a carte blanche in the fight against terrorism and biological warfare.”

Americans who remember the terrible events of 9/11 may naturally sympathize with Kenyans’ current plight. Like the United States Patriot Act of 2001, the Kenya Security Law was passed in response to deadly attacks that shocked a nation. For the US, it was 9/11; for Kenya, the final trigger was the recent Mandera attacks. Exploiting the climate of fear, the Patriot Act, like the new Kenya Security Act, swiftly moved to strengthen anti-terrorism measures. However, their are crucial differences between the two pieces of legislation. The new Kenya Security Act goes far beyond the Patriot Act by infringing on basic civil liberties and potentially violating the country’s newly-revised constitution.

While Mr. Buku may be correct in his assertion that the Patriot Act did result in widespread and well-documented abuses that sparked political scandals (e.g. Snowden, Guantanamo abuses and the CIA torture report), it featured accountability mechanisms and was open to public discourse. US Congressional re-authorization of the Patriot Act every four years acts as a safeguard. As a result, the more controversial aspects of the Patriot Act have either been amended, repealed or have expired. In contrast, the Kenya Security Act does not include similar provisions and awards too much much power to Kenyan security agencies and officials at the expense of the rights of its people.

Risk that the massive expansion of surveillance powers will be abused to justify investigations of political dissent or low-level offenses is high. The bill would expand powers of intelligence officers that were reduced in the 1990s following accusations that the Special Branch (now the National Intelligence Service or NIS) tortured activists and opposition leaders and detained them without trial. For many Kenyans, many of whom are still prominent opposition figures in Kenya today, these painful memories of the Moi years are still fresh. Thus it is no surprise that opposition leaders mounted such a fierce dissent to the legislation.

Concerns over abuse are well-founded in light of the Anti-Terrorism Police Unit (ATPU)’s long history of human rights violations. The ATPU has been linked to numerous disappearances and extrajudicial killings in the name of combatting Al-Shabbab. These abuses of power are highlighted in the recent Al Jazeera documentary Inside Kenya’s Death Squads, whichfeatures four units of Kenya’s counter-terrorism apparatus admitting that police assassinated suspects on government orders.

Empowering agencies that have shown such prior proclivity to shirk the law signals a retreat from accountability, justice and rule of law. Such action is dangerous in light of the Security Act’s often vague, ambitious and broad provisions.

The Act’s most controversial provisions include the following:

- Article 18: enables police to extend pre-charge detention for up to 90 days with court authorization. Kenya’s current law limits detention to 24 hours.

- Article 19: prosecutors do not have to disclose evidence to the accused if “the evidence is sensitive and not in the public interest to disclose.”

- Article 58: caps Kenya’s refugee population at 150,000

- Article 66: enables NIS officers to carry out “covert operations,” broadly defined as “measures aimed at neutralizing threats against national security.”

- Article 75: prohibits broadcasting any information likely to undermine investigations or security operations without police authorization and prohibits publishing or broadcasting photographs of victims of a terrorist attack without police consent

As we face the scourge of terrorism in the technological age, there are undoubtedly tradeoffs between privacy and security, however, adequate checks and balances must be established. Currently, under the new law, the NIS has unlimited powers to tap telephones without court order. In the vast majority of democratic countries - including the United States, which has one of the most aggressive counterterrorism programs in the world- such action requires a court order. The right to privacy should be respected by deferring to provisions in the Kenyan constitution that require warrants in such circumstances.

For Kenya’s 530,000 refugees, the Act has particularly serious implications. If Kenya’s refugee number is capped at 150,000, refugees will likely face refoulement. Under the new law, Kenya would be forced to expel refugees and asylum seekers. Such action would directly violate Kenya’s Refugee Act of 2006 as well as international laws including the OAU Refugee Convention.

As written, the Act tacitly makes the assumption that civil liberties such as freedom of expression and freedom of the press are an obstacle to enforcing security rather than a boon to the state's efficiency and accountability mechanisms. Instead of restricting civil society, the Kenyan government should consider enforcing existing laws aimed at combatting incompetence within the security force. The dismissal of former Interior Joseph Ole Lenko and the early retirement of former Inspector General David Kimaiyo have been good first steps, however change cannot stem from the mere shuffling of administrators. Rather, there must be a systematic approach to reforming Kenya’s security and intelligence forces.

Last month, protestors poured into the Nairobi streets to express their frustration over government’s failure to protect its citizens in a movement called Occupy Harambee. Today, Kenyans need harambee more than ever now to protect their civil liberties and to ensure that the country progresses rather than regresses to the police state of the 1980s and 1990s.

On December 23, Kenya’s opposition coalition took the first step towards such action by filing a court challenge to overturn the law. It is now up to Kenyan civil society leaders to continue to raise their voices in the press, in their communities on the streets to demand that a better balance between security and liberty.

#MyDressMyChoice: Gender and Women’s Rights in Kenya

Last Monday, a young woman walking past a busy bus stop in central Nairobi was catcalled, attacked and stripped by a mob of men. Her crime? Allegedly dressing like a “Jezebel” and “tempting” her attackers. For this, she was subjected to public assault and humiliation.

After a passerby videotaped the events and shared them online, the disturbing video became viral across Kenya. Soon after, similar videos of an attack of a woman in Mombasa emerged online.

Following the social media debate over the recent spat of incidents, the Kilimani Mums organized a “miniskirt protest” in central Nairobi to defend women’s right to choose their attire. Using the hashtag #MyDressMyChoice, Kenyan women and their male allies marched from Uhuru Park to the bus terminal on Accra Road, where the attack allegedly took place.

Deputy President Ruto has called the incident “barbaric.” Inspector General Kimaiyo has asked to the victim to come forward, so that the Police can commence an investigation into the incident.

Yet, after all the lofty rhetoric has subsided, will much have changed? It must because Kenyan women have had enough.

Despite flowery statistics showcasing female participation in government, why is Kenya a country in which the mayor of the capital city can get away with slapping the Nairobi Women’s Representative?

A country where police officers let young men cut the grass outside of the police station instead of receiving a harsher punishment for gang-raping a 16-year-old girl and leaving her for dead?

A place where a matatu ride for a teenage girl coming home from school can mean suffering the feeling of someone else’s sweaty hands creeping up your thighs?

Where policeman demand bribes to investigate rapes or outright refuse to record them?

According to a 2013 report, 1 in 5 Kenyan women is a victim of sexual violence. So when is enough and enough? Are today’s marches the boiling point for Kenyan women - mostly importantly for Kenyan lawmakers and law enforcement?

As Nobel Laureate Leymah Gbowee once said, “It’s time for women to stop being politely angry.”

On Ebola Hysteria

While headlines might make it appear that the ebola epidemic is imminent on American shores, the real epidemic at hand is ebola hysteria.

Although ebola cases in the United States have been confined to eight patients, the litany of uninformed statements and policy decisions grows by the day.

Following backlash from parents, a school in New Jersey kept two Rwandan students home. Initially, the school opted to take the students’ temperature three times a day for 21 days, however officials bowed to pressure following missives from hysterical parents. Rwanda is nearly 3000 miles from epicenter of the epidemic - more than the distance between Los Angeles and New York.

In Mississippi, parents pulled their children out of school after a principal returned from a visit to Zambia.

In Kentucky, The New York Times reported that a local woman refused to leave her house after hearing that a nurse from the Dallas hospital had flown to Cleveland, over 300 miles from her home.

In communities with many African immigrants, like my home of Washington, DC,West Africans have been subject to ostracism and outright racism.

Togba Croyee Porte, who lives in Staten Island’s Little Liberia perhaps sums it up best: “We’re fighting Ebola on two fronts: the disease in Africa and stigmatization as Africans here in America, even as we’re losing family members back at home.”

In response to the crisis, former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan stated: "I point the finger of blame at the governments with capacity… I think there’s enough blame to go around.“ He’s right. In the American case, in particular, the pernicious politicization of ebola highlights the political dysfunction of our nation.

Facing difficult midterm elections, our politicians have whipped up ebola hysteria by calling for irrational and ill-advised flight bans to West Africa while refusing to acknowledge their own complicity in the outbreak. If it were not for federal spending cuts, it is likely that we might have an ebola vaccine today. Research on an ebola vaccine was slashed from at $37 million in 2010 to $18 million in 2014.

Why have we not followed the laudable example of Cuba? The small island nation has a long history of medical diplomacy. To date, the Cuban government has trained over 460 doctors and nurses to help with the epidemic. However, due to the trade embargo, Cuba has not been able to acquire adequate medical equipment and supplies to further support its efforts to aid in this medical emergency. Over the weekend, Fidel Castro rightly called for the United States and Cuba to put their differences aside to stop the spread of the disease.

By waiting nearly five months to act, the United States and the international community have allowed the disease the spiral out of control in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea. Ebola only become relevant in American eyes when it came to our shores. It capitalizes on the fears of porous borders and on the antiquated notion of the "dark continent,” which still persists in the popular imagination. For many, Africa is still a land of coups, corruption and disease.

In reality, our fears should be more logically focused on imminent threats like the flu, enterovirus, chikungunya or even dengue fever, a hemorrhagic fever that bears some similarities to ebola and is making inroads in the Florida Keys.

Americans have been lazy on two fronts. We have been slow to respond to the epidemic and slow to call out the prejudice that is slowly eroding the decade of work to change Africa’s image around the world.

During the US-Africa Summit, coverage of the continent was paltry. Despite the presence of 50+ African leaders in our nation’s capital, talk of the event was few and far between on the Sunday talk show circuit. Yet every news program’s headline and every newspaper’s front page today features ebola. The imbalance and “disaster bias” in our coverage of Africa has never been more clear.