Check out this recent article I wrote for Okayafrica about new app Tress, which hopes to disrupt Africa's billion-dollar haircare industry. You can find the full article below and the original here.

By now it’s no secret: black hair is big business. Whether it’s New York, Paris or Lagos, black women like to experiment with their hair, and they’re willing to spend on it.

Documentaries such as Chris Rock’s critically acclaimed Good Hair explored the central role hair plays in the black community. In the United States, where the black hair industry is projected to reach $761 million by 2017, black women spend nine timesmore on hair than other racial demographics.

Euromonitor International estimates that approximately $1.1 billion of shampoos, relaxers and hair lotions were sold across South Africa, Nigeria and Cameroon in 2013. The market research firm predicts that liquid hair care market might grow as much as 5 percent by 2018 in Nigeria and Cameroon. And these impressive figures don’t even include the hugely lucrative and diverse market of hair extensions that includes everything from weaves to wigs of every texture, size and color.

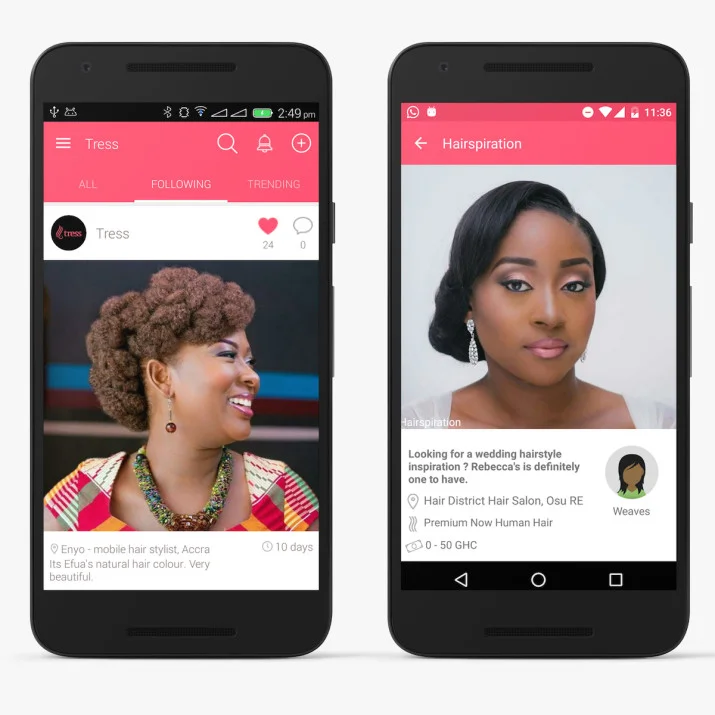

As the continent’s hair market grows, Priscilla Hazel, Esther Olatunde and Cassandra Sarfo, three female software entrepreneurs from Ghana and Nigeria, are here to help African women cash in. Their new app, Tress, is a mobile app that helps black women around the world find hair inspiration, and high quality stylists and products.

The trio met at the award-winning Meltwater Entrepreneurial School of Technology. Nestled in the popular Accra neighborhood East Legon, the school selects top graduates from across Africa every year to participate in a fully sponsored one-year, full-time, intensive educational program. In the seven years since MEST launched in Ghana, the school has successfully incubated Kudobuzz and meQasa, which have raised a combined $650,000 in the last year. Tress is the latest jewel in MEST’s line of promising startups.

The last year has been a whirlwind for team Tress. Since coming up with the concept last June, the three co-founders have dived headfirst into business and software development. Following a pilot run in Ghana last December, Tress officially launched at Social Media Week Lagos in February.

As Africa’s largest beauty market, Nigeria is one of Tress’ first two target communities. After building its network of users and salons in West Africa, Tress hopes to expand to other rapidly growing economies like Kenya and South Africa.

I catch Tress CEO Hazel fresh off of her trip to Lagos, where she spoke on a panel about technology’s role in shaping the beauty industry.

Addressing why she, Olatunde and Sarfo decided to launch an haircare app, Hazel speaks of the frustrations of trying to find accurate information about how to achieve certain hairstyles and where to find a high quality stylist.

“One of the greatest aspects of black hair is its versatility—you can do anything to it, so my friends and I, like many black women, love experimenting with our hair,” she tells me. “But we got frustrated with the lack of information. Where to go, what hair to use, what styling technique. Tress makes that information more accessible.”

When we speak, I feel like Hazel is reading my mind. Just a few days before, I lament my struggle to find someone who can do crochet braids in Accra. As I log into Tress, I locate a stylist in a matter of minutes, finding pictures of her previous work as well as a location and a number. The platform feels like a mash-up of Instagram in look and feel, and Pinterest in sheer, encyclopedic variety.

As I flip through the profiles of users and stylists, I also note with surprise the high number of natural hairstyles. Despite being majority-black, it often feels that natural hair in Accra is the exception rather than the norm. For years, in Africa’s major cities, hair extensions have been seen as a mark of status among the nouveau riche that have internalized Western beauty standards. But increasingly, like many other places in the world, the natural hair movement has started to gain momentum. On the Tress platform, the diversity in hairstyles is both astounding and refreshing.

While I find the app brilliant and straightforward, one thing isn’t immediately clear — just how does Tress plan to make money? According to Priscilla, the team plans to adopt the model of other social media giants like Instagram and Snapchat through sponsored and promoted ads after it builds a sizeable community of users.

“Down the road, we’re considering e-commerce,” she says. “We know that companies would love the opportunity to specifically target hundreds of thousands of women, and through Tress, women will learn which products they can use to achieve certain looks. But beyond companies, there are a lot of opportunities for salons–this platform could eventually help them schedule appointments and help increase their visibility.”

With the app just in its first version and yet to release on iOS, there’s more to come. Future versions will include the capability to feature by location and hair type as well as opportunities to connect with other users and form mini-communities for those with transitioning hair and more.

I, for one, can’t wait.

You can download Tress on the Google Play store today.